By Brendan Curran

|

| Brendan Curran |

When I hear the “Battle Hymn of the Republic” sung in church I start to cringe because I wonder how we make sense of lyrics about victory trumpets, terrible swift swords, and our God militantly marching on to war. In the context of our bloody history I wonder, “How many people, both soldiers and civilians, have been marched over in the name of our God?” I ask this question when I hear this song sung on Veterans Day when in our churches we might hold space to honor and hold in our hearts the people in our congregations who have survived wars.

A veteran himself, the author Kurt Vonnegut reflects on his birthday, Veteran’s Day, and reminds us of how it used to be Armistice Day—a holiday commemorating the ceasefire after World War I, the supposed war to end all wars. He writes, “We come to November eleventh, accidentally my birthday. It was once a sacred day called Armistice Day. When I was a boy, all the people of all the nations which had fought in World War I were silent during the eleventh minute of the eleventh hour of Armistice Day, which was the eleventh day of the eleventh month.

It was during that minute in nineteen hundred and eighteen, that millions upon millions of human beings stopped butchering one another. I have talked to old men who were on battlefields during that minute. They have told me in one way or another that the sudden silence was the Voice of God. So we still have among us some men who can remember when God spoke clearly to mankind.

Armistice Day has become Veterans’ Day. Armistice Day was sacred. Veterans’ Day is not. So I will throw Veterans’ Day over my shoulder. Armistice Day I will keep. I don’t want to throw away any sacred things.

What else is sacred? Oh, Romeo and Juliet, and music for instance. |

| Kurt Vonnegut |

I agree with Kurt Vonnegut when he says all music is sacred and so I find myself wondering, “What is the meaning of the terrible swift sword of God that we sing about?”

On Veteran’s day we thank our Veterans for their service and Kurt Vonnegut, by reminding us of Armistice Day encourages adding an additional statement to the expression, “Thank you for your service.” Armistice Day creates the moment to say, “Thank you dear friends for your service, AND...the war is over.” Kurt Vonnegut’s reflection reminds me of a story.

At the end of World War II, hundreds of Japanese marines and soldiers who survived catastrophes found themselves stranded, alone or in groups, on uninhibited or sparsely settled islands. Many of them survived extreme conditions and/or remote isolation. Many of these soldiers were found decades after the war had ended.

Even after decades when these elders were discovered they were prepared to continue to fight, in some cases insisting the war could not have ended and Japan could not have lost. Most gracefully, the Japanese people did not treat these men like fools for believing the war had not ended, but rather, they welcomed them back to Japan with parades for what they had done. Despite many of the soldiers’ persistent belief that they must continue to fight, they were also compassionately and gently told, “Dear brothers, Thank you, and the war is over.”

The men on the battlefields on the last day of World War I described the sudden silencing of the gunfire as the voice of God. Maybe we too hear the voice of God in silent sacred moments when we let the love of God wash over us like light and say to ourselves, “Dear soul, do not be afraid. The war is over,” whatever the war may be.

We have such a tendency to want to separate, to control, or to jump to being defensive. We cover our hearts in layers of armor because of fear. We have such a tendency to put on metal armor even though we have been shown in the resurrection of our brother Jesus how the battle is already over and we are to clothe ourselves in that light, shielded with the breastplate of love.

St. Paul reminds us that we are children of the day and that “we are to wear love as our breastplate and the hope of salvation as a helmet” (I Thess. 5:8). St. Paul encourages us to shed our worldly armor and to wear the armor of light. The question appears, “How do we wear light?”

I can only think of watching the sunrise while standing on the rocks in Maine as a child. It was one of the few times I’ve actually seen a sunrise. In the liminal space between night and day in the moment before the dawn you can hear and feel your own breathing moving in and out in tandem with the repetitive swooshing of the waves, and the sounds of seagulls and bells.

As the morning stars become illuminated you notice the gentle generosity of light. You sense a kinship with the opening life-giving power of light that touches your face, and the stars, and the sea gulls, and the rocks, and the world. Standing on the rocks quietly watching the sunrise, it becomes possible to realize how we can be as whole, as dignified, and as beautiful as the earth itself, which in quiet acceptance seems to so gracefully allow itself to be clothed in light.

The question, “How do we wear the armor of light?” jumps out of the pages of the text and I think of the people I have seen wearing the breastplate of love and the helmet of the hope of salvation. I remember my grandmother watching the sunrise with me standing with her bare feet in a tide pool, beaming, clutching a rosary, blessing the moon and talking about how our Grandfathers and grandmothers shine in the stars. I think of how those who I have seen wear the armor of light show how love, like the sunlight, gently pulls away the mantle of darkness. It melts our heart’s armor leaving us naked and open and free.

I remember the sea of candles held by thousands of people the evening before the Iraq war began. It had become clear that the bombing would start that night and so thousands of people gathered together on the foot of Dwolfe Street. It seemed there was nothing we could do to stop the bombs from falling and so they gathered and sang songs about peace. They sang about being like trees growing by the water. They sang about how we were not afraid. They sang about letting their little lights shine.

I remember the sea of candles held by thousands of people the evening before the Iraq war began. It had become clear that the bombing would start that night and so thousands of people gathered together on the foot of Dwolfe Street. It seemed there was nothing we could do to stop the bombs from falling and so they gathered and sang songs about peace. They sang about being like trees growing by the water. They sang about how we were not afraid. They sang about letting their little lights shine.

There was a mournful feeling in the crowd, but also empowering warmth in the light they created that seemed to say that the hope for a more peaceful world was blessed, and possible. Clothed in their light and held by their songs it became possible to hear in that moment a sudden silence, and a still small voice whispering, “Dear child, I am with you. I teach, ‘The war is over.’”

The people’s light seemed to preach that our hope for salvation remains our greatest protection in a world breaking under the weight of our fear and our metal armor. I learned that same night about a young woman who comes to mind when I think of our battle hymns, Kurt Vonnegut’s reminder of God’s voice in the silence, and the question of how we wear the armor of light.

The people’s light seemed to preach that our hope for salvation remains our greatest protection in a world breaking under the weight of our fear and our metal armor. I learned that same night about a young woman who comes to mind when I think of our battle hymns, Kurt Vonnegut’s reminder of God’s voice in the silence, and the question of how we wear the armor of light.

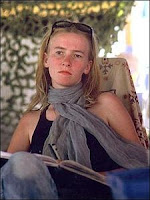

|

| Rachel Corrie |

As the crowd dispersed that night, a man came frantically running into the crowd crying, “Rachel Corrie has been killed! Please let me tell you about Rachel Corrie!” He told the crowds about the woman who as a young girl at the age of ten in her 5th grade essay wrote these words, “I am here for the children. I am here because I care. I am here because children everywhere are suffering and because 40,000 people die each day from hunger. I’m here because those people are mostly children. We have got to understand that these deaths are preventable. We’ve got to understand that people in the third world think and care and smile and cry just like us. We have to understand that they ARE us. We ARE them. My dream is to stop hunger by the year 2000! My dream is to save the people who die each day! My dream can and will come true (she says) if all look into the future and see the LIGHT that shines there.”

It was this little girl who had visions of light shining that the man spoke of when he told us of the 23-year-old woman who was crushed to death standing in front of a bulldozer blocking a well to save the only source of water for a village in the Holy Land.

I think of Rachel as a tree standing by the water. I think of Rachel as a soul who reflected the one who came for the children and who in dying declared the end of war. Seeing the haunting image of the woman Rachel at the well standing before the bulldozer clothed in the armor of light like a terrible swift sword, it can be easy to become lost in restless fears asking, “Why couldn’t the breastplate of love save her?” But I remember how all the messengers who declare the end of war and take up the breastplate of love force us to turn our faces east.

The love revealed by those who have realized themselves to be children of the day show us that we see the God who is love when we make ourselves completely vulnerable to all the awfulness and beauty of the world cross. They show us how to dawn the breastplate of love and indeed to wear it means to DIS-arm. To wear it involves opening the heart to whatever we might want to push away. It soothes us, allowing individual pain and suffering and those of the world to be held and transmuted by light. To wear it is to choose to relentlessly and joyfully surrender to a boundless love in the face of callousness and death. It means that we become in the world the voice that says, dear friends, “You are the light of the world! The war is over.” To wear the armor of light is to be lost in a love that makes no distinctions.

I think again of the generous light of sunrise and how over the ocean in Maine it touches everything and extends everywhere. When we say to ourselves, “Dear soul, the war is over,” we allow our guilt, our inadequacies, our fears, our joys, our visions, and our dreams to be held in the love that is God. As people who heard the sudden silent voice of God, we learn to hear the light of compassion as the trumpet that shall never hail retreat!

We learn to see open and outstretched arms as God’s terrible swift sword! And we learn the dance of that “God marching on” moving as children of the day with our praying grandmothers, our old men asking for peace, our prophets and our martyrs standing by the water. We move armed in light and lost in love like the whirling poet Rumi who when dancing sings, “There’s nothing left of me. I’m like ruby held up to the sunrise! I will wear the sunlight as an earring! The beauty of early dawn came over me! I saw it was pregnant with love, love pregnant with God.”

*Sermon preached at St. John’s Memorial Chapel at the Episcopal Divinity School on November 14, 2011.

**Brendan Curran is a Master of Divinity student at the Episcopal Divinity School, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

No comments:

Post a Comment